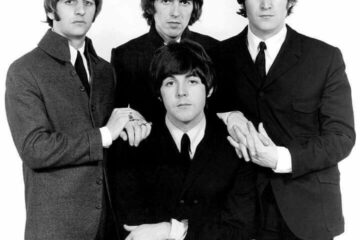

Upon the band’s dissolution, The Beatles appeared quite keen to tear down the myths and legends that surrounded the biggest band of all time. John Lennon frequently took aim at songs he thought were mediocre during his interviews, while Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr were always game to parody their previous mop-top personas.

However, it was George Harrison who did the most to reveal the human fallacies that made up the previously God-like band. A big part of that was when Harrison produced The Rutles: All You Need is Cash, the Eric Idle-led feature-length parody of The Beatles’ career arc and their subsequent transformation from scruffy Liverpudlians to cleaned-up teeny-boppers to experimental pioneers. Before and after the film, Harrison delighted in telling reporters that The Beatles weren’t as good as people thought, and he would have some choice words for the band’s catalogue.

A big target for Harrison was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band, The Beatles’ legendary LP that Harrison himself was not too fond of. “Sgt Pepper was the one album where things were done slightly differently,” Harrison said in The Beatles Anthology. “A lot of the time, we weren’t allowed to play as a band so much. It became an assembly process – just little parts and then overdubbing. After [the India trip], everything else seemed like hard work. It was a job, like doing something I didn’t really want to do, and I was losing interest in being ‘fab’ at that point.”

It’s not hard to see why Harrison was discontent: his interests were pulling away from the pop music sphere of The Beatles, and even as they continued to experiment, Harrison wasn’t happy with the direction they were heading. Ultimately, he only contributed a single song to the LP, the classical Indian tune ‘Within You Without You’.

“George wasn’t very involved in that album,” Paul McCartney would say later. “He just had one song. It’s really the only time during the whole album, the main time, I remember him turning up.”

“There’s about half the tracks I like and the other half I can’t stand,” Harrison told Entertainment Weekly in 1987. “I like most of side one, and I love ‘A Day in the Life,’ and I even like the little Indian one that I did, which is really strange and unique. But there’s a lot of them on there — ‘Fixing a Hole’ and ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ — which to me are just average.”

It’s interesting that Harrison singled out two McCartney songs. McCartney was the driving force behind Sgt. Pepper’s and contributed most of the material, with Lennon throwing in ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite’, ‘Good Morning Good Morning’ and the verses of ‘A Day in the Life’.

The rest is largely McCartney, with ‘Fixing a Hole’ and ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ displaying distinctive echoes of music hall, which McCartney would later tap into on ‘Honey Pie’ and ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’, songs that Harrison also barely hid his disdain for.

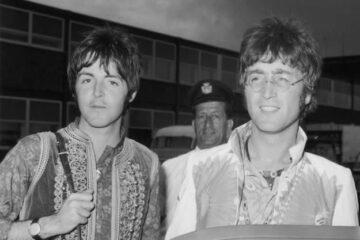

Of course, after The Beatles disbanded in 1970, the relationships among the band members became increasingly strained, particularly between Harrison and McCartney, so there was understandably a bit of needle there. Although the two had been close during the band’s early years, tensions had been brewing for some time, exacerbated by creative differences and personality clashes.

During the early 1970s, both Harrison and McCartney embarked on solo careers, and their creative rivalry continued. Harrison was particularly critical of McCartney’s solo work, feeling it lacked genuine substance. This animosity extended into their private lives, with both men often avoiding each other or exchanging barbs through the media, and Harrison’s view of Sgt. Pepper’s could have quite easily been mixed up in his own personal grievances.

Despite these issues, though, Harrison and McCartney eventually began to mend their relationship. By the mid-1970s, the two had started to reconnect, and while their friendship was never as close as it once was, they reached a level of mutual respect. The 1980s and 1990s saw occasional collaborations and more amicable interactions, especially after the death of John Lennon in 1980, which served as a sobering reminder of their shared history and mortality.