Reaching the highest height you can imagine is precisely when the realisation of an inevitable fall dawns. In life, in careers, even in morning breakfast, there’s always that lingering sense of “what’s next?”—a sense that descent will eventually follow the rising euphoria. Throw in a sprinkle of LSD now and then, and you have a glimpse of what it felt like to be in The Beatles. Even though Paul McCartney always understood their position, navigating the storm never got easier.

“No matter how well [people] do, they don’t just stay up on top all the time,” the former Beatle once reflected. “The difficulty after The Beatles was to do anything remotely valid,” he added. When the group split, as inevitable as that was at the time or with hindsight, the nature of falling from such a well-established height both frightened and fuelled a geared-up McCartney, who felt that moving on from something as world-altering as The Beatles was like sidestepping from a career in creating history to one in merely trying to live up to it.

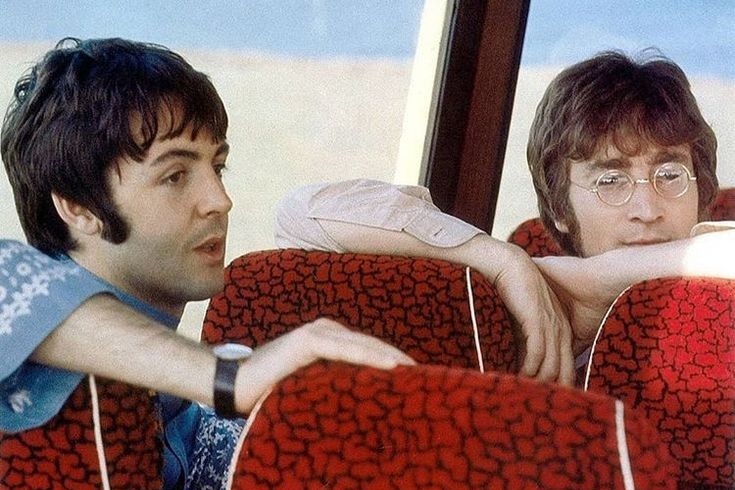

Still, as pressure mounted with all eyes on what the Fab Four would each get up to next, McCartney entered a seemingly endless game of push-and-pull with someone he once regarded as his best friend, as John Lennon sought to explore his own musical terrain while pushing away any sense of distraction that reminded him of his past or tethered him to expectations he no longer wished to fulfil. In short, the embarrassment of riches that came with being in the world’s biggest band made him feel more distant from himself than ever, and he longed for an escape, even if that meant squashing any lasting entanglement with his former musical partner.

But that was then, and McCartney has had many years to reflect on his achievements and shortcomings, likely reaching various conclusions pointing to the futility of feeling regret or guilt. While Lennon and McCartney may have reconciled before John’s tragic death, the tumultuous years that followed—filled with the ebb and flow of emotional turmoil—likely rendered any lingering negativity irrelevant in the face of a simple truth: together, McCartney and Lennon changed the world.

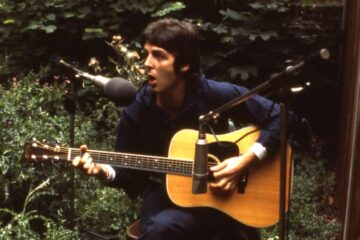

The beauty of that fact is that even two years after Lennon’s death, McCartney knew it to be more true than possibly anything else. The first album he released after his friend’s passing, Tug of War, already held a sense of poignancy long before its release. Although shelved for a couple of months to allow McCartney space to breathe in the thick air that came post-Lennon, the album showed a more emotionally charged side to the singer, one that went beyond anything anyone deemed possible, with a deep reflection and vulnerability that captured the weight of loss and the struggle for peace.

The album’s title track proved that more than anything, this project was a reunion, not just because McCartney enlisted help from George Martin and Ringo Starr, but because of how heavily he filtered Lennon’s presence into the music. Aside from the sombre and melancholic lamentation McCartney delivers as he navigates the claustrophobia of a “tug of war” partnership, it also feels entirely epiphanic in the way McCartney almost attempts to envisage what a better world might look like.

He delicately oscillates between enabling dreamlike allusions, including the lines, “In another world

/ We could stand up on top of the mountain / With our flag unfurled,” and, “In years to come they may discover what the air we breathe and the life we lead are all about / But it won’t be soon enough, soon enough for me.” Although the surface reading dredges up feelings about McCartney’s relationship with Lennon, it also presents his surroundings’ potential with a hue similar to Lennon’s exploration in ‘Imagine’.

Both songs appear similar because they channel hope and optimism and share numerous thematic and emotional parallels, mainly in their reflective qualities and the message-driven approach both musicians took when delivering their tributes. In both songs, Lennon and McCartney also share a more visceral albeit overt sense of awareness about the forthcoming descent that follows a long high, the idea that greater things can be possible if the right circumstances are fostered and nurtured.

While Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ presents a more overt charm and optimism about the future of the world, ‘Tug of War’ maintains a powerful sense of forward-thinking, offering a nuanced exploration of reconciliation and renewal amid grief. Although McCartney might not have layered his optimism as explicitly as Lennon did, addressing his loss while contemplating the next chapter was essential for him, especially when continuing his relentless journey of waiting to fall aimlessly from the top.