A little over 61 years ago, four young lads from Liverpool released their first single. From then on, in a matter of years, and in a strangely unassuming manner, they would change the world as we know it. For millions, if not billions of people, The Beatles are the first artists we can comprehend—in our early childhoods, the rest of culture blurs into a faceless milieu of creations without creators while the Fab Four stand out as something distinct and important.

The melodies, words, and moments that the humble lads crafted are woven into our yesterdays, todays and our tomorrows, too. They have transcended art and become a fixture of modern society. When you’re four, ‘Yellow Submarine’ is not some dusty tune from the 1960s but rather a quirky chant used to bond with classmates, and when you’re 64, ‘A Day in the Life’ might be anchored in time by the weight of memories attached to it, but it still feels as seafaringly fresh and pioneering as ever.

Rather than forming an inescapable Groundhog Day where The Beatles have been arbitrarily crowned the ruling monarchs of culture, their presiding influence connects generations, extolls beauty and keeps the prelapsarian dream of the 1960s alive in some small but inviolable sense. They may have called it quits only eight years on from their debut single, but they have never truly gone away; the end was a full stop of sorts, but the postscript of their golden sentence still rambles on. And now that end has fittingly shifted into the present in a tangible fashion.

‘Now and Then‘ is more than just a new Beatles song. This is evidenced by the fact that millions will eagerly huddle around today to hear it—people of all ages, colours, creeds and so on, bound by the simple commonality of interest in the most transcendent band of all time. This is a feat to rejoice in an age pitted by indifferent division. In many ways, this makes the last song they’ll ever offer their most definitive.

Firstly, all four of them are patently present in the new track. Uniquely, this has always been the case with The Beatles. There is no leader of the gang or ‘best Beatle’, as Macca says himself, “Making good music in a band is all about chemistry.” They have always typified that tenet and the secret of their transcendence is that it has also been the meta-message they have shared with the masses: the joy of communion and interaction. “All you need is love” might sound like barefaced naivety, but when four mates in their mid-20s are broadcasting that to one in 16 people on the entire planet via a ground-breaking satellite link-up back in 1967, there seems to be more than a grain of truth to it; a poppy simplification, yes, but a truism all the same.

And that broadcast also hits upon another element that makes ‘Now and Then’ distinctly “Beatley”, as McCartney puts it: back when they first emerged, in an age where the technological fix seemed to be broken following the scourge of war, they seamlessly incorporated progression into their art, picking up where Pet Sounds left off, to illuminate a bright alternative future for the world. Now, once more, when love seems to be in short supply and fears mount around dreaded AI, the band has looked on the bright side, transfiguring something baleful into a tool for beautiful art.

Along the way, they have had tremendous support—once more, this is another key element of The Beatles. They were never truly just the Fab Four; the endless list of folks dubbed the so-called ‘Fifth Beatle’ is evidence of this. ‘Now and Then’ sees Giles Martin step into his father’s old footsteps, creating an awesome orchestral score; Peter Jackson and his team are akin to Enoch Light, Brian Wilson, Geoff Emerick and the likes who provided the band with new possibilities to play with and pioneer into a truly artistic conception.

And then there’s you, the eager fan tuning in to turn a new song that utilises a form of technology that has actually been deployed a good few times already into a historic occasion. And this is proof that the Beatles have never just been the Fab Four; they’re so much more than that. Whether it was the hysteria of Beatlemania that pushed them on, the cresting wave of the counterculture that they rode, the great scores of maestros they incorporated into their ranks, and a million other factors, they stood at the confluence of a generation of inspiration and opened themselves up, not just creatively, but to the world, with a mantra that fittingly opens the teaser documentary for the new track: come together.

So, when tasked with reviewing the new Beatles song, the last Beatles song at that, over six decades on from the first, can you really just muse over its quality or the technical means that brought it to us? This isn’t a song in that typical sense; it is a celebration of culture and the joyful utopia it can sail our way in a coracle of hope through the seas of dogged reality.

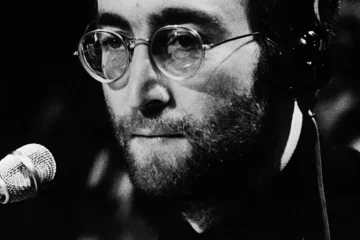

From the second the count-in graces us, there is an upswell of emotion. That reaction is purely indicative of our expectations. Hell, a count-in is one of the most commonplace things in pop, but this time, it carries a weight that the track continues to bear gracefully on its robust shoulders throughout. In the ilk of one of John Lennon’s brooding mid-70s solo tracks paired with the majesty of Abbey Road, the song carries a darkness, a dense intrigue and introspection that ensures it is not subsumed by the hype and rendered an indulgent gimmick sustained by our current fetishisation of nostalgia, but rather a sincere, touching exploration of Lennon’s pleading mindset, and the exultant release of making music with friends.

As ever with The Beatles, it is a piece of art created with unrivalled chemistry, even via the conduit of AI. This is evidenced by the wondrous syncopation of McCartney’s bass that rumbles perfectly beneath his old pals’ stabbing piano jabs. And the extra lashings of care that have gone into crafting a perfectly pitched score rather than wheeling out something half-cooked for the cash-in. But the evident creative flow of the musicology is only part of the wallop, all the same.

Of course, the track is a beauty – from John Lennon’s tear-jerking tones to the lulling lure of George Harrison’s slide guitar solo, Ringo Starr’s humility to fade into the background and facilitate everything with a singular rhythm, and Paul McCartney’s ability to orchestrate the magic like a man who has mastered music to such an extent he can make it dance to his command like a marionette – but beyond that there is a story that we’re all part of, a continually unfurling tale that has no farewell, just a facet of culture passed on in the folk manner that spawned it, to brighten our days with a fanfare of celebratory colour every now and then.