The world has already proven that the title of The Beatles‘ 1968 album doesn’t matter at all. We’ve all engaged in a kind of global Mandela effect or historical rewrite as the album is mostly widely known as The White Album. It’s actually, and uninspiringly, simply called The Beatles. But it was almost named neither of those things.

The White Album, as I’ll choose to call it throughout this piece, is a fascinating creation. It is totally and utterly a product of its circumstances, which were messy. By the end of the 1960s, The Beatles were collapsing. Personally, professionally and creatively, their relationships were falling to bits under the strain of drugs, business decisions, fame and each other’s personal lives. “That was the tension album,” Paul McCartney said of the record.

By these late-stage records, the collaboration that had once tied the band together had combusted. John Lennon and Paul McCartney, once a fierce-some duo, were barely even friends. George Harrison was starting to get antsy with the desire to spread his wings or at least be listened to more. And Ringo Starr, well, Ringo was still just happy to be there. Really, by the time it came to making this album, all four members were living in their own worlds, existing largely separately and working in their own lanes.

But that’s precisely why their working title might have been the perfect fit. Initially, the album was going to be called A Doll’s House. It fits easily within one’s mind: a big psychedelic house, similar to the imaginary one the band lived at in their film Help!, but this time, rather than existing in one large spanning room, all sharing the same space like the best of friends, their quarters are blocked off. They might still be forced to share the same abode, but the dolls each had their place.

There is also a clear comment on their thoughts towards fame. Their positioning as dolls feels like an outright reaction to how they felt like they were being handled, controlled by some higher powers and forced to move and do whatever they wished. Once again harking back to the scene of them messing about in a big dreamhouse in Help!, they were willing and jovial dolls then like shiny new toys. But by 1968, they were broken.

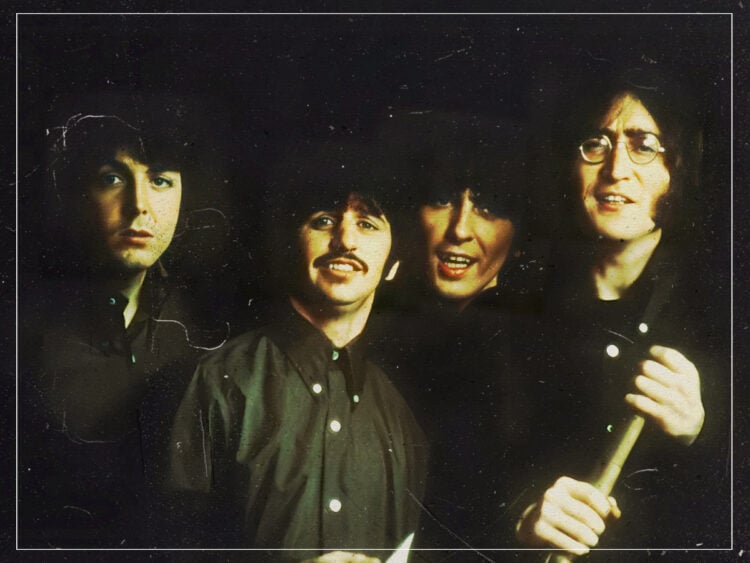

The original artwork makes that point clear. In a design from John Patrick Byrne commissioned to match the initial title, the Fab Four are painted with an uncanny, avant-garde air. All the members have deep, blacked-out eyes and clear frowns, wearing their unhappiness right there on their faces. As they were crawling towards the end of the line, coming together to make the album largely reluctantly but under pressure from their team to hold it together a little longer, the dolls didn’t want to play anymore.

After the bright and colourful eras of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour, the band wanted to differentiate the next release with a starkly different look. But A Doll’s House feels like it would have been a perfect title to capture the messy, trippy, slightly dark air of the album, perhaps even giving it more form.

It could be said that the record is the exact opposite of a concept album. As the members refused to compromise on the tracklisting, all demanding space for their songs as the tracklist grew and grew, there is really no thematic or sonic through-path. It is a random collection of songs created at the time, perfectly summarised upon release by Lester Bangs, who said, “It was the first album by The Beatles or in the history of rock by four solo artists in one band.”

Under the moniker of A Doll’s House, the record could have taken shape as a strange anthology, dropping in on randomised stories and moments, much like a child’s imagination does. As so many songs deal with characters, such as Bungalow Bill, the ‘Piggies’, Martha and ‘Sexy Sadie’, all of these people would have had a home to inhabit.

The title was abandoned at the last minute as another British band, Family, got in there first with their album Music in a Doll’s House. It was a moment that would change The Beatles’ history.